Billy Durant’s middle name should have been Positive–he invariably took the most positive view of any circumstance, especially recessions.

Billy Durant’s middle name should have been Positive–he invariably took the most positive view of any circumstance, especially recessions.

In those days they didn’t call them recessions, of course, they called them Panics. (Hmm… considering their unpredictability and the pain and devastation they cause, panic probably is a better name than recession. Perhaps we should go back and call it the Panic of 2008. But I digress.)

The year 1893 brought America the best and worst of times: the exuberant optimism of the Columbia Exposition in Chicago, but also the Panic of 1893. Billy’s response to the economic setback was to create a new brand of buggy with ABC Hardy. It took off and added to Billy Durant’s fame and fortune.

In 1907 the country had another panic. Automobile sales slumped, but Billy Durant simply leaned on suppliers to extend more credit and kept the Buick assembly lines rolling. When the economy recovered (like it always does) Buick was the only manufacturer with adequate inventory, so it ended the year as America’s number one auto maker. Billy’s positivity once again carried the day.

However, positivity can be a two-edged sword… especially when debt is involved. Billy bought Cadillac in 1909 for a bargain price (two times earnings) but he had to pay cash. General Motors didn’t have the money so Billy went deeply into debt. Mr. Positivity started with debt and had no fear.

He should have. The economy unexpectedly hiccupped ever so slightly in 1910, the year after the Cadillac purchase. General Motors had no margin for error. Again, Billy’s positivity dictated uninterrupted production. This time, GM ran out of money.

Through a set of circumstances worthy of a best-selling novel, GM was bailed out by Billy’s nemesis: Wall Street Money.

Wall Street wasn’t (still isn’t) nearly as smart as they love to see themselves portrayed. Not only did they repeatedly miss out on opportunities to finance what would become the world’s largest industry, but when they bailed out GM, they missed out on yet another opportunity.

How?

By not understanding what they got in return. Lee, Higginson, the investment bank leading the bailout, was (like most investment houses of the time) pretty much a bond house. For them the dramatic breakthrough was moving from government and railroad bonds into “industrial” bonds. At the time industry (as we know) it was a new phenomenon, like social media today. Investors regarded industries (like autos) with some suspicion, even after J.P. Morgan put together U.S. Steel. Industrial bonds, then, tested the limits of riskiness. Industrial stocks? Not even worth wasting a thought over.

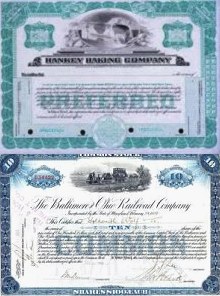

No surprise, then, that Lee, Higginson and the others essentially gave General Motors a five year mortgage bond as their bailout. In return they received 6 percent… and some stock (split of course between preferred and common) as a bonus.

When investment bankers put up the money for a buyout, they rarely keep the securities they get. Like a used-car dealer, the simply turn around and sell them… for a profit, of course. In fact, in order to assess whether they should get into a deal, they pre-sell it to their investor clients. If they get good interest, they do the deal, but if their clients indicate they’re not interested, the bank usually bails.

What’s Remarkable

Once the GM bailout bankers saw up close how well Billy had put GM together, they sold almost none of the bonds to their clients– they held onto those bonds themselves. The bailout package was “sold out” in a matter of hours as all participants decided to hang on to everything.

Part of that “everything” was the bonus stock offered in addition to the 6 percent interest.

This is where it gets interesting (and where the Big Banks’ vaunted expertise got shown up yet again). While the (bond-centric) banks held on to their bonds, they weren’t nearly as attached to the bonus stock they (in their minds, at least) got “for free.” The fact that its price languished around $60 only added to their perception that the stock was essentially worthless.

Billy knew better. He understood what the bankers couldn’t see: the automobile market would keep growing until every house had a car. They (literally) laughed at him about that. George Perkins, a J.P. Morgan partner, told Billy to his face he had better stop spewing nonsense like that if he ever hoped to get taken seriously on Wall Street.

And so… when Billy began plotting his comeback he offered to take these bankers’ “worthless stock” off their hands. He knew they valued preferred stock higher than the common, so he offered them less than market price for their common. They were only too happy to turn the paper they disregarded into cash, and probably thought even less of the soft-spoken and slightly build maverick who could be so stupid as to pay real money for the paper.

Their surprise came when Billy Durant took GM back from them in no small part with the stock they so readily sold him. Stock which by then had soared north of $500 a share. The common stock, see, was the only stock with a vote. When the bankers wanted to use their preferred stock to block Billy they came up empty.

They didn’t understand the difference between preferred and common stock… and Billy made them pay.

How did he pull that off? Read the book and see. 🙂