Dabblers tinkered aplenty with horseless carriages as the 1800s wound down. The Dureya brothers tried to make a business of it, as did Alexander Winton of Cleveland. In 1899 Winton was the best selling maker of automobiles (with less than 400 sold) based largely on his reputation as a winning race car driver. Such was the state of the industry when the 20th century dawned. What shifted it to a higher gear was a single event: the 1900 New York auto show.

Dabblers tinkered aplenty with horseless carriages as the 1800s wound down. The Dureya brothers tried to make a business of it, as did Alexander Winton of Cleveland. In 1899 Winton was the best selling maker of automobiles (with less than 400 sold) based largely on his reputation as a winning race car driver. Such was the state of the industry when the 20th century dawned. What shifted it to a higher gear was a single event: the 1900 New York auto show.

The newly formed Automobile Club of America organized it to draw all manufacturers together in one place and present the object of their interest to the public. They had high hopes. The new century was an exciting time in America: every day brought something new, from David Buick’s white enameled bathtub to Mr. Crapper’s indoor flushing toilet.

You’ve been told, and may even have subscribed to the notion, that the world has never seen as much change as what we witness in our lifetimes. Don’t believe that for a second. The 30-year period from 1880 to 1910 saw more change than in any time in human history. It’s not only gadgets, although that period saw a flood: electricity, photography, radio, phonograph, telephone, automobiles, airplanes, and the aforementioned indoor plumbing, to name only a few. This period brought us the biggest change in mankind’s history.

The Really Big Change

People, as long as we know, lived where they earned their living. As late as the mid-1800s even people in towns lived above their places of work: smiths, bakers and general store owners, for example. And they typically owned their own business. Apprentices would serve for a while, but usually with the notion that they would someday hang out their own shingle.

But the industrial revolution, with its railroads and factories, brought man a new concept: a job, where an employer took the business risk and you simply drew a paycheck. And the notion of a commute. Today we take for granted getting up, having breakfast and then commuting to a job. In the evening, we pack up, hit the road (or rail) and return a few miles home. We lose sight that this concept is barely more than a hundred years old–a mere speck in the thousands of years of recorded human history.

The advent of the twentieth century marked perhaps the zenith of the pace of change, and an era of unmatched optimism. New York City was just warming to the second Madison Square Garden, a monument to all things new and exciting, so where better for the Automobile Club of America (another new thing) to have the show? Incidentally, Bill Metzger, one of the early leading lights in Cadillac and the Detroit auto industry, was one of its organizers of the auto show. (He would eventually go on to become the M in EMF, one of the top auto manufacturers a decade later.)

The date the organizers picked was auspicious: two weeks before the annual horse show, scheduled for the same arena. Many papers mentioned that prominently, musing in print as to whether this was a portent of more changes to come.

The 1900 New York Auto Show

Saturday, November 3 dawned fair and cool–perfect weather for New York society to flood the doors to witness the full array of over sixty manufacturers displaying their latest, greatest and up to datest models. Celebrities made sure the papers mentioned their presence: the Astors, Vanderbilts and the like.

The auto show itself was surprisingly compact–too compact, many people felt. Because there was no precedent for such a thing as an auto show, organizers arranged it like a horse show: with a fairly broad track surrounding the exhibits. The horse thing pervaded the horseless carriage thing further: most newspapers put reports of the show in their sports section, usually next to the horse race reports. If you’re interested, here is a full page from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (courtesy newspapers.com) dealing with the show… and other sports to give you a flavor for the era and event.

The track allowed several events to take place, showing the audience the capabilities of these newfangled machines. Imagine the noise and the smoke from all those running engines! It was the sound and smell of a new century… and the crowds loved it.

The Cars

The debate was still on in full force then: would steam be the way to go? Electrics? Or the internal combustion engine? (To say gasoline-powered would technically be incorrect, because several steam cars used gasoline as their fuel.)

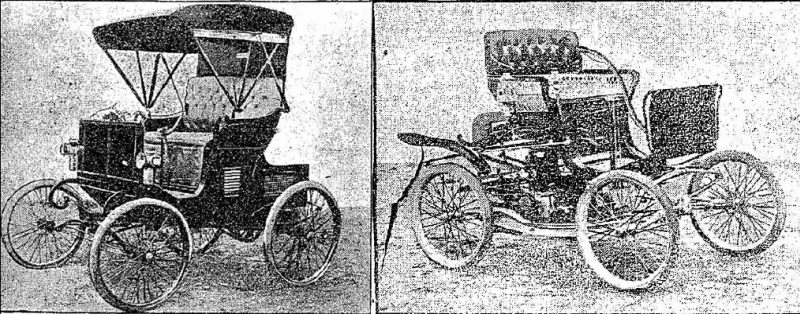

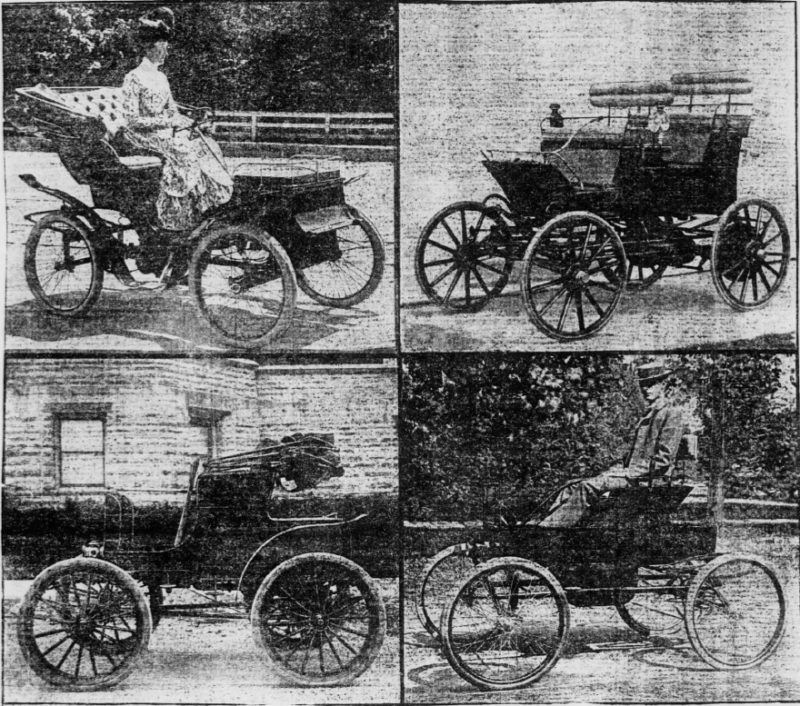

Here are a few of the internal combustion cars, none of whose names will mean anything because none of these manufacturers survived.

Frail and spindly, wouldn’t you agree? No wonder Billy Durant saw no threat to his horse-driven vehicle empire. Most first-generation cars were unreliable, giving rise to the popular saying when a horseless carriage stood stranded by the roadside: get a horse!

The Future

France was the leading nation for automobile design and popularity at the time, led by a firm called De Dion-Bouton. When ABC Hardy went to Europe to get out of Billy’s telephone reach, he visited their factory and came away convinced that the automobile was certain to make the carriage business obsolete. Here is one of their 1900 models (image courtesy YouTube):

Less frail, less experimental loooking… but much more expensive. This is the type of thing which gave rise to the notion that only rich people could afford automobiles. Only after Ransom Olds’ Curved Dash did the idea take hold that mere mortals could also own cars.

The show itself was a success from all perspectives: manufacturers sold plenty of cars, the organizers made a tidy profit, the media appreciated something to gush about and the soma attendees were impressed enough to vow to return if it were held the following year.

One of the few non-gushers was Billy Durant. He only went to hang out with his Flint buddies, because by 1900 he spent most of his time in New York to follow the stock market. Everything he saw only reinforced his disdain for the horseless carriage.

Little did he know how his tune would change… 🙂